While talking about stereotype has become rather boring, stereotypes themselves have not gone out of fashion, nor have they lost much of their ability to stand in for real people and real issues. Stereotypes fill films and literature, and allow their audience to quickly follow plots and conflicts without much explanation of character motivation or social context. They also fill academic work and journalism for the same reason. Whether through cultural appropriation, or misrepresentation in literature or journalism, the results are the same: stereotypes help us all consume ideas, and often that includes consuming the labor, lives, and lands of Indigenous peoples.

Surely such a statement needs to be explained. So let’s talk about how stereotypes work.

Since 1492, the Indigenous peoples of North America have been described in ways that served genocidal goals. Columbus applied the term Indios to the Natives, a label that has stuck for over 500 years with only slight variation to become “Indians.” This label ignores, and erases, the diversity of Indigenous peoples across the hemisphere. There were, and are, hundreds of different languages, cultures, forms of art, dietary practices, systems of belief, and social institutions across North and South America. The use of a single term is part of the strategy to control Indigenous peoples by ignoring their specific relationships to lands, cultures, histories, and each other.

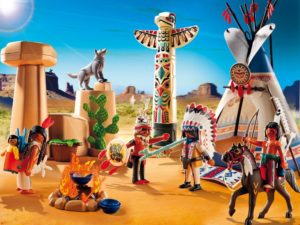

This stereotype lumps all Indigenous peoples together with one term, and by now even under one image: “the Indian.” This overgeneralization makes tribes interchangeable; no matter their differences, one tribe can stand in for any other tribe, or all tribes can be treated the same. Further, the signs and symbols used to indicate “Indian” have become a mishmash of images drawn from a variety of unrelated groups.

That’s how we wind up with Woodlands style clothing mixed with Plains style housing next to Northwest Coastal art in a Southwestern setting, like this:

These symbols, removed from their traditional settings and haphazardly thrown together, should be meaningless nonsense. Instead, the result means “Indian.” I could probably walk into any classroom anywhere on Earth, ask that the students draw a picture of an “Indian,” and know exactly what every drawing would look like. That is how prevalent the stereotype has become; a misnomer of “Indian” from 500 years ago has become a global phenomenon.

These signs of “the Indian” reduce our existence to a small list of features, most often based on old photographs (such as by Edward Curtis, who was more concerned with staging “authenticity” than representing actual Indigeneity). What’s worse, is that outsiders then demand that we display these signs in order for our Indigeneity to be noticed. In other words, we sometimes have to uphold an inaccurate image of ourselves so that outsiders can recognize our “authenticity.”

Even worse, the prevalence of these stereotypical notions of what counts as “authentic” allow outsiders to believe that they are experts in what an “Indian” is. Many of us have had the experience of non-natives questioning our authenticity, or even telling us how to “properly” conduct a ceremony, or how to be more “traditional.” Usually their interventions rely on shame as a means to change our behavior so as to make themselves more comfortable claiming authority over what counts as “tradition.” No matter how well-intentioned, outsiders acting as cultural police can only serve to disempower insiders.

Even more perniciously, the reduction of Indigeneity to “race”—especially through the myth of blood quantum—has empowered non-natives to ask us “How much Indian are you?” and then evaluate our comparative worth according to our answers. A few years ago, I was driving back to Minneapolis from Maine. A toll booth operator looked at me and said, “Oh, they let you leave the reservation today?” I didn’t answer, so she asked, “Are you full blood?” I replied in my usual way to that question: “I don’t even know what that means.”

“Oh, come on!” she said. “You’re not full blood; just look at you.”

Anyone who claims to be able to tell if someone is Indigenous or not by looking at them is a fool. I am probably as irritated by fakes and wannabes as any other person, but after working with Indigenous peoples from all over the continent I can wholeheartedly report that first impressions are often wrong. Even their actions might not tell the whole story, because I have seen people trying to revitalize their traditions in awkward (or even offensive) ways simply because they lack elders or good teachers. I can only hope that their community figures out how to better include them as they work towards decolonization together.

In some cases, non-natives who get good at performing the stereotype, receive more accolades than those of us who are doing amazing things on the world’s stage, but aren’t dressing the (stereotypical) part. These performers take up space, preventing better representatives from being seen and heard. This contributes to the pressure on Indigenous peoples—be they activists, authors, artists, or academics—to somehow show their “authenticity,” and the easiest way to do that is to play to these stereotypes.

Johnny Depp honors Barack Obama with an eagle feather headdress

Outsiders who expect us to fit their stereotypes often dismiss our existence as inauthentic. This mischaracterization is what lies behind, for example, Jesse Ventura’s 1999 statement against the 1837 Treaty that guaranteed off-reservation fishing rights, when he said that, “if those rules apply, then they ought to be back in birch-bark canoes instead of with 200-horsepower Yamaha engines with fish finders.” What he is really saying is that he thinks there are no “authentic Indians” anymore. According to this argument, if the present-day Ojibwe no longer fit his stereotype of “Indians,” then treaties no longer need to be honored.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Board, founded in 1935, was created to protect “authentic” Indigenous art and promote a market that supported Indigenous artists. That sounds great, but in practice it often meant non-native experts determining what counted as “authentic.” Those criteria included quality of craftsmanship, the “race” of the artisans, a reliance on handwork and simple tools, and other markers of primitivity. Innovation in style, technique, and tools meant a loss of authenticity in much the same way that the “dilution” of “race” does. “Authenticity” was measured by how well art fit a stereotype, and this was (and is) legislated and policed at the Federal level to serve the market interests of consumers. Outsiders (and some insiders) continue to conflate “authenticity” with racial purity and static traditional practices, even refusing to acknowledge Indigenous art that is too colorful, too abstract, or shows too much influence from Mexico (which is especially ironic, since Mexico is also Native North American land). These were precisely the comments by art critics and curators who rejected the work of Patrick DesJarlait and Oscar Howe.

As Oscar Howe wrote to the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa OK, after his work was rejected as “not Indian” in 1958:

Who ever said that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art than pretty, stylized pictures. There was also power and strength and individualism (emotional and intellectual insight) in the old Indian paintings. Every bit in my paintings is a true, studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting, with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child, and only the White Man knows what is best for him? Now, even in Art, ‘You little child do what we think is best for you, nothing different.’ Well, I am not going to stand for it. Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art….

So we can see how stereotypes get in our way as Indigenous people. They disrupt our political relationships with outsiders, and those misunderstandings can get in the way of our rights, our livelihood, and our way of life.

Sadly, because of colonial disruption of education, spirituality, social life, and economy, some people have been left with little more than stereotypes to fill in the missing aspects of their lives. Instead of being raised knowing that Indigenous identity is, first and foremost, a political identity shaped by history, language, and tradition, many of us only know an “Indian” identity based on an aesthetic—a style or fashion. Artistic expression has always been an important part of Indigenous identities, but those styles arise from our relationships as a people through our history, our languages, our music, and our lands. There is a story behind each piece of art we wear or each activity that we do; that story may be personal, or it may be common to a community. These stories are relational, and therefore political. There has always been a lot of intertribal contact, and so we can see cultural influences, but those influences have stories behind them, as well. Sharing influences with your neighbors is not the same as having definitions of “authenticity” imposed on you, and certainly not the same as coercive assimilation policies intended to, as Pratt said, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Those of us involved in revitalizing or maintaining traditions have to fill in those missing pieces with patience and kindness, working from a place of strength and responsibility as reflected in our traditions, so that all of us can find our place and role in these stories.

It is not enough for us to point out historical inaccuracy or misrepresentations. It is not a matter of increasing awareness and sensitivity, or encouraging diversity and inclusion. Better education about Indigenous history and culture is needed, but the persistence of these stereotypes is only partially fueled by ignorance of facts. Stereotypes will only lose their force when the relationships among groups of people are respectful instead of exploitative. Most of the power of these misrepresentations comes from an ongoing investment in colonial settler supremacy based on economies of extraction. Under colonialism, ignoring Indigenous rights to lands, language, cultural expression, and our continued existence literally pays benefits.