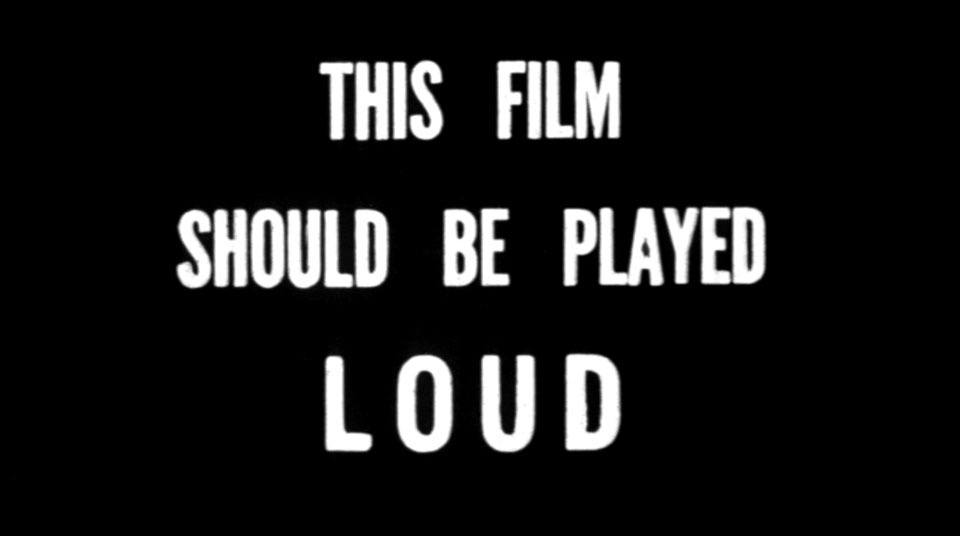

I’m here to talk about Abel Ferrara’s 1979 film The Driller Killer, in which a NYC artist named Reno Miller (played by Ferrara, listed as Jimmy Laine), under pressure to deliver on a commissioned painting, unpaid bills, as well as a crumbling domestic situation, kills a lot of homeless men on the streets.

The painting he is trying to finish is a stylized bison, large in scale, which I take to represent a primitivist urge that he can’t fulfill. He is also beset by the annoying presence of a punk band that takes up a rehearsal space in the apartment building. I take this to represent a different sort of primitivist urge, the primitivism of punk that becomes yet another failure of his as the singer steals his remaining girlfriend after his other girlfriend, left Reno for her former husband.

The film opens in a Catholic church. Reno and his girlfriend Carol (Carolyn Marz) were called down to see a homeless man being sheltered there.

The church has been keeping the old man safe after some kind of crisis resulting in amnesia. A nun says he doesn’t know who he is, or where he comes from, but he had Reno’s name and phone number in his pocket. Reno approaches him as he is sitting in the front pew of the church, and the organ music stops after Reno crosses himself and moves to sit in the pew. The old man, with his long white beard and hair, doesn’t look at Reno. Reno slides slowly over, staring at the old man, and his hand slowly moves across the railing towards the old man’s hands. Suddenly, the old man grabs Reno’s hand, and Reno panics and runs away.

The ways Reno was looking into the old man’s face as he slid across the pew clearly indicate that there was some recognition going on, and perhaps even a desire to be recognized in return. Recognition is not the same as contact, and while Reno may have many questions for the man who may be his father, it is clear he is not ready to make an actual connection with the homeless man. Reno rejects the suggestion that the homeless man may be his father in a series of classist slurs when Carol asks if he knew the homeless man.

Reno: “Who knows? Some fuckin degenerate bum wino, I don’t know.”

Carol: “You didn’t recognize him at all?”

Reno: “Why should I recognize him, man?”

…

Carol: “Well, you never knew your father”

Reno: “Carol, please, baby, what are you saying?”

Carol: “Nothing”

Reno: “Yeah, nothing, please. Don’t even say something like that. The cat’s some degenerate, some bum, some wino, some nobody, that’s all. I don’t even know what the hell we’re doing down here in the first place.”

Carol: “Well, why did he have your name and phone number on a piece of paper in his pocket?”

Reno: “Probably found it in the garbage while he was lookin’ for his lunch”

Through the rejection and denial of his father, we begin to see how what Reno actually hates is rootlessness, he hates not belonging. Thus, his anxieties are settler anxieties.

They then make out in the cab as they ride over to retrieve their third, a blonde named Pamela (Baybi Day), who is watching The Roosters perform. Tony Coca-Cola (D.A. Metrov, who did many of the paintings in the film), the lead singer and guitarist, is dressed in a street glam fashion, wearing a pale foundation, heavy eye shadow, and bright red lipstick, with exaggerated shadow blush on his cheeks. Pamela is transfixed by him. They’re playing an insistent, driven form of blues-based music, crafted out of a stripped-down arrangement of traditional rock instruments with an almost parodic disregard for pitch, meter, or melody. I honestly think this is one of the best depictions of a New York punk band I have ever seen.

A few points about punk and modern art

Hebdige, in Subculture: The Meaning of Style, says:

It would seem that those approaches to subculture based upon a traditional semiotics (a semiotics which begins with some notion of the ‘message’ – of a combination of elements referring unanimously to a fixed number of signifieds) fail to provide us with a ‘way in’ to the difficult and contradictory text of punk style. Any attempt at extracting a final set of meanings from the seemingly endless, often apparently random, play of signifiers in evidence here seems doomed to failure. P117

However, the postmodernist concern with the potential of polysemy in especially the most confusing and/or taken for granted cultural expressions was an attempt to rescue meaning-finding by people trying to understand meaning-making. The focus fell onto the position or positions of the speaking subject, and identifying the process of meaning-making from that position within a structure of language and society. This allowed meaning-finders the possibility to imagine finding socially valuable, and even radically transformative, meaning-making processes. Unfortunately, an appeal to nihilism as radical negation of meaning (and meaning-making) tended towards elision, or outright erasure, of the colonial contexts of cultural signification. Hebdige takes a, by now, old understanding of radical signification, correct though it is, and crashes it into the dark matter underlying all cultural expression in a by then (as it is now) colonial context, when he says:

For instance, we have seen how all subcultural style is based on a practice which has much in common with the ‘radical’ collage aesthetic of surrealism and we shall be seeing how different styles represent different signifying practices. Beyond this I shall be arguing that the signifying practices embodied in punk were ‘radical’ in Kristeva’ sense: that they gestured towards a ‘nowhere’ and actively sought to remain silent, illegible. P 120

For Reno, and punk (and, for that matter modern and postmodern art), the underlying dark matter is primitivism. Rejection, or parody, of bourgeois musical traditions and standards often entails cultural appropriation from primitive Others, even outside the genre of punk. Sometimes those appropriations can be somewhat self-conscious or even self-aware, and here I am thinking of appeals to tribal, pre-Christian, or post-apocalyptic imaginaries like Killing Joke, especially for their Fire Dances album, or the mythos of Voivod cultivated by the French-Canadian metal band of the same name, or even Jim Morrison’s entire Lizard King persona being based on the claims of being haunted by dead Indians. The Roosters seem to take most of their inspiration from the blues as distilled through mainstream media and layers of unrecognized cultural appropriation, and during a key sequence in the film, The Roosters are playing a version of Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn” theme, while the bassist is wearing a T-shirt that simply says “Dakota” across the chest in a military-style stencil font.

Punk is primitivist not just because of mohawk hairstyles, rejection of Victorian sexual mores, or its rejection of national narratives of progress. It is primitivist in its selective, if not quite strategic, appropriations from primitive cultures. As in modern art, which first resourced internal primitives as resources for aesthetic renewal and then through and because of colonialism increased its compass globally, punk drew ambivalently from the internal margins of its society first, such as gender nonconformity, racism/antiracism, and fascism/antifascism, and then expanded to the colonial frontier as its imaginary. This is undeniable in consideration of the influence of ska and reggae on punk. While those connections might highlight the ambivalences over race and empire within the punk subculture, that undeniability also serves to mask the colonial anxieties within punk itself. The gesture is not towards “nowhere,” as Hebdige argued, and the silence must be made to speak if we want to understand to coloniality that becomes smuggled in by such “radicalism” that is, in the end, not radical at all. If the gestures actively sought to be silent and illegible, the motivation for that silence and illegibility is a denial of the colonial context of the gestures, and of those both making and interpreting the gestures.

Reno, despite being in New York city during what has come to be romanticized as the golden age of punk, is having none of it. When The Roosters move in to the same building as Reno, it enrages him.

Pamela brings The Roosters to the apartment building, and the supervisor allows them to move into a space for $500 a month, in cash.

Reno: “Who are these clowns, anyways?”

Carol: “They’re called The Roosters, Pam knows the lead singer, Tony Coca-Cola, from the club. They’ve rented out the sixth floor to rehearse.”

…

Carol: “They really sound good on their album.”

Reno: “Album? These guys have an album? What, are you kidding? If I heard this on a record, I’d quit painting in protest. Listen, I’m going out where I can get some peace of mind.”

Next, he’s shown drawing homeless men in his sketchbook as he watches them on the street. He both hates them, and is inspired by them. The same can be said about Tony Coca-Cola, as later, during his murder of the art dealer, Reno dresses and makes himself up much in the same way as Tony Coca-Cola appeared on stage at the beginning of the film, even putting on some of his girlfriends’ clothes. As he finishes getting dressed, there is a shot of him framed very much like the cover of the “Sticky Fingers” album by the Rolling Stones. He is enacting the same impulses of domination evident in the patriarchical, classist, and appropriative actions of colonialism.

A few points about class and connection

Reno and his live-in partners are faced with mounting bills, with the phone and electricity about to be turned off. As he questions the long-distance phone charges, Carol and Pamela claim various calls as their own. Carol simply says “That’s mine” or “Their mine,” and Reno questions how she could talk to LA for over two hours. Pamela, on the other hand, indicates who she was calling, her mother in Houston and her sister in Philadelphia. In this way, Pamela points to her relationships as justification of the expense of long-distance phone calls.

Unable to pay these bills, and upon learning phone service would be cut the next day, Reno throws the telephone out the apartment window. (This sentence and the last paragraph lack gravitas and impact for readers who haven’t held an old landline phone.)

In the context of Reno not knowing his father, and not willing or able to connect to the homeless man who may be his father, Carol and Pamela have social and familial connections. In the film, we only see Reno calling his art dealer, first to ask for an extension of the deadline and a monetary advance on the sale of the buffalo, and later to lure the dealer to Reno’s apartment to be murdered by Reno. The only other time we see him on the phone is a failed attempt to reach Carol after she returned to her husband, and then an imagined conversation Reno carried out with, in his mind, Carol, while only hearing a dial tone in the telephone receiver. Even their relationship is portrayed as an uneven distribution of communication, with Reno talking to one or the other of them most of the time, and whenever a three-way conversation is attempted, it fails miserably.

As Carol sleeps, Reno and Pamela are talking about how their futures will change with the sale of the painting.

Reno: “We sell this buffalo, everything is gonna change. We’re gonna have enough money to do what we want when we want to. We’ll be able to get everything we need.”

Pamela: “The first thing I’m gonna get is snakeskin boots.”

Reno: “Oh, yeah, man, we’re gonna get lots of clothes. We can get a boat. Buy ourselves some motorcycles, and we’ll go away. Go to Jamaica. Morocco. We can go to Nepal. Wherever we are, man, we’re gonna go out every night.”

As he states these wishes, the buffalo is staring at us, the audience, in a slow zoom in to its eye. The buffalo knows Reno’s class aspirations are out of his reach, just as the buffalo knows that Reno’s mental state is collapsing much like the rest of his life.

He begins to have nightmares about his father, homeless men, and a power drill. The nightmare tells him the problem isn’t the painting, the problem is the entire city. Reno, fearing homelessness due to unpaid rent and bills, begins to see how the structure of urban modern life is blocking him from the success and recognition he feels entitled to. He sees belongingness in the creative class as a goal, and begins to feel that his own familial roots in the homeless population of the city are holding him back. Homeless people, in his view, do not belong in the city, they do not deserve to exist, and must be erased so that he can be free of the familial limitations and connections that keep him from attaining the status of a self-made, creative genius.

This echoes the American frontier, and frontier attitudes toward that other perceived barrier to progress: The Indian. According to the frontier hypothesis, the heroic entrepreneurial spirit that came to define a particular American identity was forged through violent struggle against wilderness. That struggle meant whites could partake in primitivist aesthetics and expressions, including violence and lawlessness, in order to achieve the greater good of colonial social progress, economic growth, and the spread of civilization. In fact, the superiority of technology in tools of violence is celebrated as evidence of and justification for the elimination and subjugation of The Indian, and anyone else who gets in the way of the individual creative genius, the entrepreneurial spirit, of the frontier hero.

And, as we know, the arts has a role in class subjugation and elimination through gentrification. Reno seems unaware of these impulses, though, as he describes the economic benefit of artistic success, seemingly just out of reach for him.

Reno finds his technology boost via a commercial on the television for a portable battery pack that can be worn as a belt around the waist. The advertisement becomes part of his vision for personal and aesthetic redemption. This will allow him to wield an electric drill out on the streets of New York, to massacre homeless people. Homeless people, here, represent settlers who do not belong, because they are not contributing anything to social or economic progress. Reno’s hatred of them is a projection of his own failure as an artist in contributing anything back to the society that, he feels, owes him a living.

He eventually thinks Carol also gets in his way. She is the most practical one of the thruple, and has been covering the group’s bills through her alimony payments. She tries to convince him that the buffalo painting is done so that it can finally be sold. This sends Reno into a verbal rampage.

Carol: “It’s finished. I mean, I know you know we need the money, so why don’t you just face up to it?”

Reno: “Oh, so it’s finished. Thank you. It’s finished. Since when did you become such an expert on painting? I mean, you’re telling me it’s finished? What do you know about painting, anyway? Really, what do you know about painting? I’ll tell you what you know about painting, man. You don’t know nothin about painting, man. You know what you know about? You know about how to bitch, and how to eat, and how to bitch, and how to shit, and how to bitch, but you don’t know nothin about painting, so don’t tell me when this is gonna be done. I’ll tell you when it’s gonna be done. And about the money, man, I don’t wanna hear about that money, all right? Cuz it’s all you talk about, it’s all the other one talks about, that’s all I hear from that fag art dealer uptown. And I don’t want to hear it cause the sound of that word, man, it drives me crazy. You know what I think about money, anyway? I’ll tell you what I think about money, see this? [he tears up some currency] This is what I think about money. This. All right? So go ahead. You ready? Throw it up in my face. Come on, you’ve been waiting to say it. Say it. Say it! Say how you been paying the bills, how we’ve been spending your money, how you picked up the rent last month, huh? What do you want me to do, get on my knees? You want me to kiss your feet? Well, forget it man, because this place has been here long before you got here and it’s gonna be here long after leave, all right? So don’t tell me about money, and don’t tell me about painting, and don’t tell me when this thing is gonna get finished, all right? Cause I’ll tell you when it’s gonna get finished. In fact, you’ll be the first to know. I’ll come and tell you, man. I’ll come up to you wherever you are, even if you’re sleeping, I’ll sneak up to you, man, I’ll whisper right in your ear, man, I’ll say ‘It’s done!’”

Reno’s need for control over himself, his domestic partners, and his art is all unravelling. As The Roosters rehearse, he tries to paint. He is mixing his reds, distracted. When he looks into the buffalo’s eye, he sees himself covered in blood, shaking it from his face and hair, accompanied with sound like screaming. Reno’s image echoes Tony Coca-Cola’s earlier appearance, but lacks any of Tony’s self-control and cool.

He ultimately carries out a lot of murders over the next few nights, during the course of which he finishes the buffalo painting, and also accepts a commission from Tony Coca-Cola to paint a portrait of the singer. It is a necessary deal, and seems to be a chance to reverse his fortune financially and artistically, even as it also represents an unwelcome compromise of his artistic integrity and desire to be unbothered by The Roosters. As he is modeling, Tony Coca-Cola spews pseudointellectualisms and reads a book he doesn’t himself seem to understand, and he kisses Pamela. If Reno learned one thing from having to listen to The Roosters as he tried to paint, it was how to somewhat tune out Tony. Reno’s last act of autonomy is choosing to be nonresponsive to Tony’s blathering requests for communication, intended to understand Reno’s artistic process. Tony even calls Reno’s silence scary.

At another point in the film, Reno is perched atop a cistern or water tower on the roof of his apartment building. From there, through a set of binoculars, he watches homeless people on the street, an emergency scene in a park, and a murder of a pedestrian by stabbing. He takes this all in as evidence of the sickness of urban life, all the while he is, literally, perched on a reservoir of modern convenience also made possible through colonial and imperial violence. He sees what his nightmare told him he would see, out on the street, but fails to see the danger he is in himself, and also fails to recognize the continuity of violence that he is a part of. This is the contradiction of Reno, an artist who so desperately wants to belong, does not see how he is already a part of colonialism through cultural appropriation as both an artist, as well as a settler feeling entitled to a comfortable living, its innocence upheld through denial and erasure of how ongoing imperial and capitalist violence provides that comfort.

Artists, writers, and philosophers have mined primitivism as a resource for aesthetic and political renewal for centuries. So have boy scouts, survivalists, outdoor education programs, and punk rockers.

But the twinned primitivism of cultural appropriation—on one hand the noble and romanticized buffalo, on the other the ignobility of punk rock—both fail to bring Reno any sense of creative or existential renewal. Instead, he violently targets settlers whom he sees are failing to contribute anything to society: homeless men. However, he doesn’t see that these murders, like his art, are also not contributing anything to society. Murdering homeless men doesn’t eliminate street crime, or poverty, or advance any other measure of so-called progress. Neither does his art do anything to change the circumstances of imperial, colonial, and capitalist oppression that keep him from feeling any meaningful sense of belonging. Thus, he embodies a warped desire for decolonization that can only be expressed in the same violent fashion against a scapegoated Other that has been deemed, on colonial terms, to be a barrier or burden to both personal and societal progress.

But this murder spree against the homeless doesn’t change Reno’s circumstances at all. So he lures the art dealer to his apartment under false sexual pretenses, and murders him with a drill. This is merely a vengeance killing, Reno’s payback after being emasculated by the art dealer when he repeatedly called the buffalo painting “worthless” in front of Carol and Pamela. But the murder of the art dealer also does nothing to bring him any real sense of belonging or accomplishment.

Pamela finds the art dealer’s body, and Reno catches her as well. While her fate is left somewhat ambiguous, in that we don’t see Reno kill her, it is hard to imagine any other possibility since Pamela not only brought The Roosters in to the apartment building, she suggested that Reno should have sex with the art dealer to sell his painting, and she also had sex with Tony Coca-Cola in the studio while Reno was painting Tony’s portrait. At any rate, by this time Reno has all but given up on finding any sense of belonging on his own terms, not as an artist, not as a man, not as a partner. He only has one move to make, and while he thought the only tools he had working for him (after his paint and brushes have apparently failed him) were a power drill and a battery pack, he had one other tool at his disposal: appropriation.

Reno finally appropriates the role of husband, specifically Carol’s husband. Now reunited, and attempting to rekindle their romance, Carol takes a shower as Stephen husband prepares some tea to bring into the bedroom. Reno enters the home and kills Stephen with his drill, the noise covered by the running water.

Reno then hides under the bedcovers, and Carol speaks to him as if he were her husband, while a church bell rings in the distance. Reno responds in tired-sounding grunts. She turns out the light, and we are left with a black screen for nearly a full minute, the last third of which we hear Carol begging “Stephen” to come closer to her in the bed. It’s one of the most tense scenes I can recall on film.

Glib conclusion

Looking at this film through an Indigenous Studies lens provides insights into how The Driller Killer, a film presumably made without so much as a single thought about Indigenous people, lands, history, or issues, can reveal myriad connections and echoes to the structures, images, and technologies of colonialism. The context of colonialism has, seemingly, infected all forms of cultural expression, such that it may be unethical to ignore not just how that context has shaped art and film and literature, but how it has shaped a tendency to ignore the colonial context as we made literary criticism of these expressions. So as we work to examine “Indigeneity in the Horror Genre,” we must remain open to the possibility of finding Indigeneity in some rather unexpected materials, including the negative space and silence that is foundational to coloniality itself.